Subscript and superscript can make all the difference when it comes to chemical formulas.

Subscript and superscript can make all the difference when it comes to chemical formulas.

Molecules, compounds, and other chemical structures include more than one atom. Sometimes, there are multiples of one particular atom.

For instance, anhydrous aluminum chloride features one atom of aluminum joined to or combined with three atoms of chlorine. Its chemical formula reflects this: AlCl3.

But – simply knowing how to use a number in this instance is not enough. It is essential to know the proper use of subscripts and superscripts.

Subscripts in Chemistry

Notice the number 3 is written as a subscript, or a number that is smaller than the other text, and below the normal text line, in the formula for anhydrous aluminum chloride above. The concept of a multiplicity of atoms is conveyed by this use of a subscript.

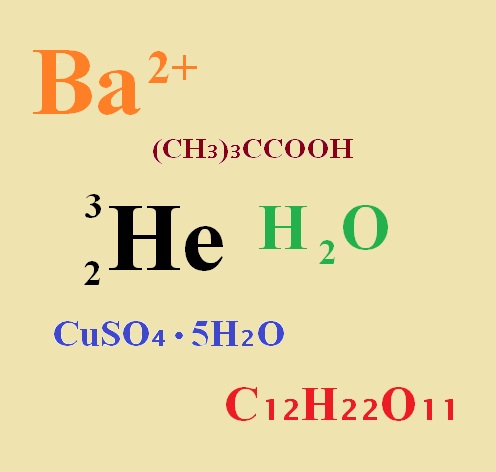

You can also write the formula for Sucrose or table sugar, using chemical symbols and subscript numbers. There are 12 carbon atoms, 22 hydrogen atoms, and 11 oxygen atoms in sucrose – the chemical formula for table sugar looks like this: C12H22O11.

Sometimes parentheses are used to characterize a particular structure, as follows:

(CH3)3CCOOH

The above molecule is pivalic acid. We occasionally refer to this molecule as trimethylacetic acid, since, visually, the molecule contains 3 methyl groups CH3–. Written in its most elemental form, the formula for pivalic acid is C5H10O2.

Another more complex structure – acetone, or dimethyl ketone – exemplifies the beneficial use of parentheses.

CH3(CO)CH3

How are the parentheses beneficial? In this instance, it is because the oxygen atom is not connected to either the leftmost or the rightmost carbon atom but only the middle carbon atom. Acetone’s chemical structure could also be written (CH3)2CO or (CH3)2C=O.

Superscripts in Chemistry

Atoms often occur as combinations of isotopes. Hydrogen, the simplest gaseous element, has one electron and one proton in all its atoms. However, a small percentage of hydrogen atoms also have a neutron in the nucleus. This form of hydrogen atom is, naturally, heavier than the hydrogen without a neutron. To distinguish them, a superscript is employed. The letter H with a left-justified superscript symbol 1, written 1H, represents hydrogen containing one nucleon – that is one nuclear particle – a lone proton. On the other hand, the symbolism 2H represents the deuterium form of hydrogen, which contains 2 nucleons – one proton and one neutron. If there is a subscript below the superscript, it indicates the number of protons, only.

Sometimes a superscript is used in connection with atomic charge or ionization. Some atoms lose an electron or electrons and bear a positive charge, for example +2. If instead there is an excess of electrons, the (+) symbol becomes a (–) symbol. A metallic barium ion can lose 2 electrons to become Ba+2.

Water of Crystallization

Sometimes compounds crystallize from water solution with some specific amount of water becoming part of the crystal structure. This water is called water of crystallization. One of the best-known examples is copper sulfate, CuSO4. If prepared free of water, copper sulfate is almost white. Add water then crystallize it, however, and it becomes the pentahydrate. Since 5 molecules of water combine with each molecule of copper sulfate, the structural formula is written CuSO4•5H2O.

Subscripts and Superscripts: Up, Down, Left, or Right

To summarize, then, the location of the number next to an atom’s shorthand symbol is very important. The location indicates what that number refers to – number of molecules, number of atoms, number of nucleons, number of protons, and even the number of electrical charges an atom bears.

Note: You might also enjoy The Simple Difference Between Alkanes, Alkenes, and Alkynes

References:

This is VERY important information for anyone beginning chemistry and very clearly set out.